By now, most of us are pretty familiar with the process for adding managed beans to an XPages app: go to faces-config.xml and add a <managed-bean>...</managed-bean> block for each bean. However, JSF 2 added another method for declaring managed beans: inline annotations in the Java class. This wasn't one of the features backported to the XPages runtime, but it turns out it's not bad to add something along these lines, and I decided to give it a shot while working on the OpenNTF API.

The first thing that's required is a version of the annotations that ship with JSF 2. Fortunately, annotations in Java, though ugly to define, are very simple, and each one involves only a few lines of code and can be added to your NSF directly:

javax.faces.bean.ManagedBean

package javax.faces.bean;

import java.lang.annotation.Retention;

import java.lang.annotation.RetentionPolicy;

@Retention(value=RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface ManagedBean {

String name();

}

javax.faces.bean.ApplicationScoped

package javax.faces.bean;

import java.lang.annotation.Retention;

import java.lang.annotation.RetentionPolicy;

@Retention(value=RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface ApplicationScoped { }

javax.faces.bean.SessionScoped

package javax.faces.bean;

import java.lang.annotation.Retention;

import java.lang.annotation.RetentionPolicy;

@Retention(value=RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface SessionScoped { }

javax.faces.bean.ViewScoped

package javax.faces.bean;

import java.lang.annotation.Retention;

import java.lang.annotation.RetentionPolicy;

@Retention(value=RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface ViewScoped { }

javax.faces.bean.RequestScoped

package javax.faces.bean;

import java.lang.annotation.Retention;

import java.lang.annotation.RetentionPolicy;

@Retention(value=RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface RequestScoped { }

javax.faces.bean.NoneScoped

package javax.faces.bean;

import java.lang.annotation.Retention;

import java.lang.annotation.RetentionPolicy;

@Retention(value=RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface NoneScoped { }

The more-complicated code comes into play when it's time to actually make use of these annotations. There are a couple ways this could be handled, and the route I took was via a variable resolver. Note that this code requires my current branch of the OpenNTF API, though a mild variant would work with the latest M release:

resolver.AnnotatedBeanResolver

package resolver;

import java.io.Serializable;

import java.util.*;

import javax.faces.context.FacesContext;

import javax.faces.el.EvaluationException;

import javax.faces.el.VariableResolver;

import javax.faces.bean.*;

import org.openntf.domino.*;

import org.openntf.domino.design.*;

import com.ibm.commons.util.StringUtil;

public class AnnotatedBeanResolver extends VariableResolver {

private final VariableResolver delegate_;

public AnnotatedBeanResolver(final VariableResolver resolver) {

delegate_ = resolver;

}

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

@Override

public Object resolveVariable(final FacesContext facesContext, final String name) throws EvaluationException {

Object existing = delegate_.resolveVariable(facesContext, name);

if(existing != null) {

return existing;

}

try {

// If the main resolver couldn't find it, check our annotated managed beans

Map<String, Object> applicationScope = (Map<String, Object>)delegate_.resolveVariable(facesContext, "applicationScope");

if(!applicationScope.containsKey("$$annotatedManagedBeanMap")) {

Map<String, BeanInfo> beanMap = new HashMap<String, BeanInfo>();

Database database = (Database)delegate_.resolveVariable(facesContext, "database");

DatabaseDesign design = database.getDesign();

for(String className : design.getJavaResourceClassNames()) {

Class<?> loadedClass = Class.forName(className);

ManagedBean beanAnnotation = loadedClass.getAnnotation(ManagedBean.class);

if(beanAnnotation != null) {

BeanInfo info = new BeanInfo();

info.className = loadedClass.getCanonicalName();

if(loadedClass.isAnnotationPresent(ApplicationScoped.class)) {

info.scope = "application";

} else if(loadedClass.isAnnotationPresent(SessionScoped.class)) {

info.scope = "session";

} else if(loadedClass.isAnnotationPresent(ViewScoped.class)) {

info.scope = "view";

} else if(loadedClass.isAnnotationPresent(RequestScoped.class)) {

info.scope = "request";

} else {

info.scope = "none";

}

if(!StringUtil.isEmpty(beanAnnotation.name())) {

beanMap.put(beanAnnotation.name(), info);

} else {

beanMap.put(loadedClass.getSimpleName(), info);

}

}

}

applicationScope.put("$$annotatedManagedBeanMap", beanMap);

}

// Now that we know we have a built map, look for the requested name

Map<String, BeanInfo> beanMap = (Map<String, BeanInfo>)applicationScope.get("$$annotatedManagedBeanMap");

if(beanMap.containsKey(name)) {

BeanInfo info = beanMap.get(name);

Class<?> loadedClass = Class.forName(info.className);

// Check its scope

if("none".equals(info.scope)) {

return loadedClass.newInstance();

} else {

Map<String, Object> scope = (Map<String, Object>)delegate_.resolveVariable(facesContext, info.scope + "Scope");

if(!scope.containsKey(name)) {

scope.put(name, loadedClass.newInstance());

}

return scope.get(name);

}

}

} catch(Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

return null;

}

private static class BeanInfo implements Serializable {

private static final long serialVersionUID = 1L;

String className;

String scope;

}

}

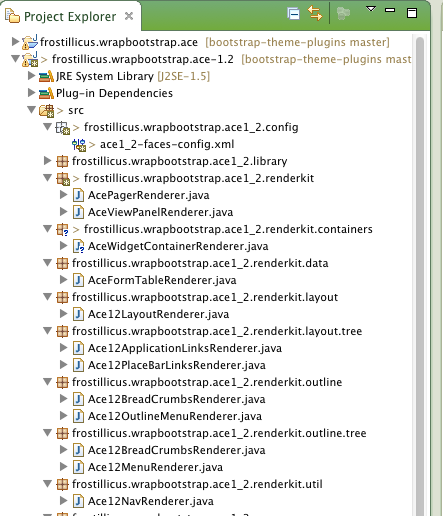

faces-config.xml

<faces-config>

...

<application>

<variable-resolver>resolver.AnnotatedBeanResolver</variable-resolver>

</application>

</faces-config>

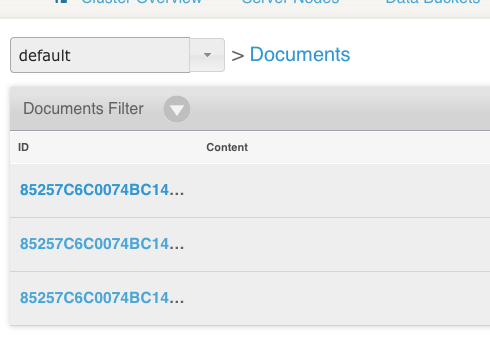

This is not efficient! What happens is that, whenever a variable is requested that the main resolver can't find (or is null), the code goes through each Java class defined in the NSF (not in plugins, the filesystem, or in attached Jars) and checks if it contains the @ManagedBean definition. Fortunately, the worst of this is only incurred the first time (according to the duration of applicationScope), but that one-time process is still something that would get linearly slower as the number of Java resources in your app increases.

Now, there are still other features of the actual JSF 2 implementation that this doesn't cover, particularly @ManagedProperty, but it can still be useful on its own. In practice, it lets you ditch the faces-config declaration and write your beans like this:

package bean;

import javax.faces.bean.*;

import java.io.Serializable;

@ManagedBean(name="someAnnotatedBean")

@ApplicationScoped

public class AnnotatedBean implements Serializable {

private static final long serialVersionUID = 1L;

// ...

}

I plan to give this a shot in the next thing I write to see how it works out. And regardless of future use, it's a nice example of the kind of thing that gets easier with the OpenNTF API.